The human brain perceives, categorizes, evaluates, and therefore processes the vast number of stimuli.

The amount of information and the value of these, if considered, is staggering (Ogas & Gaddam, 2023). The world that we evolved in, with all those colors of freshly bloomed flowers, sweetly dancing pitched notes of songbirds, satisfaction of lightweight caresses of one’s lover bombards us with an overwhelming array of stimuli. Although this seems to be intense and excessive, it represents only a fraction of the total information we are exposed to. Although it is the challenge that addressing how the human brain accomplishes this, thanks to the insightful contributions of complexity theory, we fortunately have some answers.

Complexity is a mathematical theory that proposes the nonlinearity of a structure, ones whose emergent properties or behaviors cannot be explained solely by the nature of its individual components (Capra & Luisi, 2014). These systems do not change or create behaviors in a predictable manner, thus they are nonlinear. In other words, behavior of the building blocks of any system, say, the firing neurons in the human brain, and their interactions are insufficient to explain the system’s overall behavior, say, the cognition of cooperation among animals. Since this model seems to explain both the organization and the structure of organisms, their cognitive processes, and even some aspects of physical systems in the universe, it is a well-respected and growing area with the contributions of scientists from diverse disciplines.

For a particular system to be considered complex, it is assumed that several phenomena need to be observed (Mitchell, 2009). First, it is the emergence of complex collective behavior, which basically says that there is an emergence of collective output that is not observed when the components of the system are taken or observed individually, and the overall behavior is hard to predict. Second, these systems signal and process information, in other words, information spread across the network of individual components of the system, which may be the most crucial aspect of these systems. Finally, these systems adapt: the collective behavior, led by information processes, changes or favors particular patterns in order to increase the survival or the existence of the very system. For example, the reason why any neural system performs these actions is that the information processing enhances the survival of the organism in which the very neural system dwells (Mingers, 1991). The human brain, since it is an extremely complex structure, generates a collective output through information processing and signaling between the neurons, from which all mental processes stem, ultimately increasing the chances of survival of an organism. Given all this, it is now appropriate to answer the question: ‘How does this theory specifically explain the very nature of the brain’s mechanism?’, which can be addressed through automata theory.

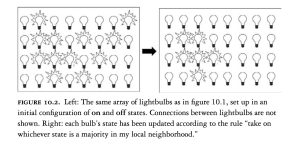

In the 1950s, John von Neumann, a legendary figure in many fields of science, developed the theory of cellular automata to explore if the brain functions like a computer and if cognition can be computed. Cellular automata can be understood through a simple model: Imagine an arrangement in which light bulbs were used to represent the individual components of the system, which can communicate only with their neighbors. And for clarity, they have two states, on and off. The current state of a bulb, therefore, is determined by the general rule and the states of the neighbors (Figure 10.2, from Mitchell, 2009).

After several tries are executed, a scaled-up version of this arrangement yields an output that is incomputable. It is simply because of the fact that the previous states of the bulbs serve as feedback for the subsequent states, which in turn creates a never-ending feedback loop. Another case is that the feedback loops create patterns, which are the very same patterns we saw in neural systems, although this is a very vulgar version of a neural network.

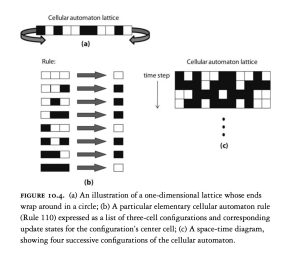

These fascinating aspects of patterns in complex systems captivated the attention of a young researcher at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, the brilliant physicist Stephen Wolfram, who was working on different versions of cellular automata (Figure 10.4, from Mitchell, 2009). In order to understand the most basic form of it, he created two-dimensional automata in which every individual in the layout is only neighbored with two other individuals. He then formulated three-cell configurations (Figure 10.4b), which mathematically allowed for 256 rules (23 = 8 configurations and therefore, 28 = 256 rules). With randomly assigned initial configurations of cells, he ended up with fascinating chaotic patterns, and with the emphasis that the chaos that is observed in the Figure 10.6 (from Mitchell, 2009), is obtained upon the configuration of very simple rules.

In his controversial book A New Kind of Science, Wolfram speculated that he had discovered a fundamental law of nature (Wolfram, 2002). He further proposed that the universe textured on an ultimate model of a cellular automaton, whose computation is in turn the cause of all the physical phenomena. Although these are mere speculations, they are very important for our purposes since they point out a crucial aspect of our understanding of complex systems.

What do all these discoveries demonstrate? A prominent paper showed us that the mechanism of non-centralized communication among individual parts of a given system could be the foundation of how the brain works in detail. Melanie Mitchell—whose ideas are greatly appreciated in this text—and her colleagues wrote the aforementioned paper, which investigates how a cellular automaton can compute to reach a solution for a given problem (Mitchell et al., 1996). They explored the local majority vote problem, in which the initial configuration of cells must collectively determine whether the overall majority is black or white, and present this as an output (e.g., if there are 87 black and 113 white cells, the output should be white). However, the challenge was that even though one can write a code which each cell modifies its state based on the majority of its neighbors, it fails to solve the problem (Figure 2, from Mitchell et al., 1996).

Upon confronting this dead-end, they adopted a genetic algorithm to solve the problem. The GA is a set of ‘genetic imprints’ that generates near-optimal behavior by mimicking natural selection.

In other words, the GA evolves, using mechanisms that are outside the scope of this paper, providing one of the most efficient sets of codes or ‘genes’ after thousands of generations of calculations. The most effective genome generated true answers, with those kinds of shapes that seem meaningless in the first glance (Figure 4, from Mitchell et al., 1996):

As Mitchell (2009) noted, they were initially stunned, and could not assign any meaning to these patterns. However, after intensive inquiry and with the help of Jim Crutchfield, they came up with the idea of ‘particle’, a concept that they borrowed from physics. Surprisingly, it appears that somehow, although it seems that the individual cells of the automaton were not able to acquire from or signal to the information those who are very distant, the system as a whole manages to do so through particle-like structures, such as theta and mu, as shown in Figure 5 (from Mitchell et al., 1996).

In other words, the system used individual cells as information-carrying components to produce complex behavior; this means the CA used groups of cells to differentiate different regions and behave as though the boundaries were signals, even though the behavior of none of the individual cells was meaningful or purposeful on a smaller scale (Mitchell et al., 1996). This finding, therefore, indicated that with the power of evolution, even the two dimensional, relatively vulgar arrangement with very few states and configurations, can produce complex phenomena, let alone basic calculations. Thus, it seems that an extraordinary arrangement, with billions of individual components, and thousands of states and configurations, can create fascinating phenomena. It is not a coincidence that nearly two thousand years ago, Galen proposed that “Men ought to know that from the brain, and from brain only, arise our pleasures, joys, laughter and jests, as well as our sorrows, pains, griefs and tears…” (Kandel et al., 2013).

All things considered, the mechanism of the human brain would most probably be relying on wave-like automata, in which vast amounts of information are signaled through billions of neurons, whose numerous states are both chemically and electrically determined. It is still, as far as we know, the most complex structure that we have ever inquired about.

References

Capra, F., & Luisi, P. L. (2014). The systems view of life: A unifying vision. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511895555

Kandel, E. R., Schwartz, J. H., & Jessell, T. M. (2013). Principles of neural science (5th ed.). McGraw Hill Professional.

Mingers, J. (1991). The cognitive theories of Maturana and Varela. Systems Practice, 4(4), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01062008

Mitchell, M. (2009). Complexity: A Guided Tour. Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, M., Crutchfield, J. P., & Das, R. (1996). Evolving cellular automata to perform computations: A review of recent work. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Evolutionary Computation and its Applications (EvCA ’96). Moscow, Russia: Russian Academy of Sciences.

Ogas, O., & Gaddam, S. (2023). Journey of the mind: How Thinking Emerged from Chaos. W. W. Norton & Company.

Wolfram, S. (2018). A new kind of science. Wolfram Media.